By AbuSatar Hamed

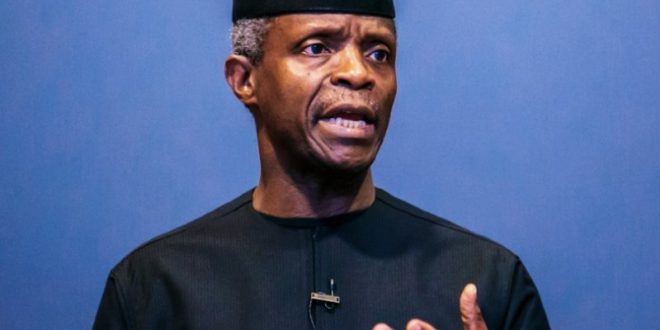

The Vice President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Prof. YemibOsinbajo has said that classification of Nigerians as “indigenes” and “non-indigenes”, is Nigeria’s form of divisionism and has long contradicted the aspirations towards unity in diversity.

Osinbajo stated this on Tuesday July 30, 201 at the 70th Anniversary celebration of the Lagos Country Club, saying “All that should matter in evaluating ourselves, is where we live and fulfill our civic obligations. This is why our Social Investment Programmes are being administered on the basis of residency. The eligible beneficiaries were selected based on their states of residence and none was discriminated against on any basis.

According to a release signed and made available to StarTrend Int’l magazine by Laolu Akande, Senior Special Assistant to the President on Media & Publicity, Office of the Vice President, the No 2 citizen in Nigeria said: “I was at an event in Lagos where some old boys of Kings College, a Federal Government college were gathered. So, there was in their midst, Adebayo Ogunlesi, Christian Yoruba gentleman, who founded one of the most successful private capital firms in the world, there was Keem Bello-Osagie, Muslim from Edo State, once a major investor in UBA and Etisalat, Emir of Kano and former CBN Governor, Sanusi Lamido; they were all classmates and they have continued to work together promoting each other over the years.”

“The classification of Nigerians as “indigenes” and “non-indigenes”, is our own form of divisionism and has long contradicted our declared aspirations towards unity in diversity. All that should matter in evaluating ourselves, is where we live and fulfill our civic obligations. This is why our Social Investment Programmes are being administered on the basis of residency. The eligible beneficiaries were selected based on their states of residence and none was discriminated against on any basis.”

Below is his full speech at the event:

SPEECH BY HIS EXCELLENCY, PROF. YEMI OSINBAJO, SAN, GCON, VICE PRESIDENT OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA, ON THE OCCASION OF THE 70TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION OF THE LAGOS COUNTRY CLUB, ON THE 30TH OF JULY, 2019.

Protocols.

It gives me great pleasure to join you all in celebrating what is a truly remarkable milestone for the Lagos Country Club. It is no exaggeration to say that this is one of the most reputed voluntary associations and recreational institutions in Lagos and indeed, Nigeria, going on seven decades and still going strong. Congratulations!

I am also glad to note that the Club continues to advance the noble goals for which it was founded in 1949, notably to promote family values, use sports and other recreational activities to deepen social solidarity and promoting inter-ethnic and inter-racial understanding among people.

I shall be speaking for a few minutes on the topic, “Promoting National Cohesion as a means of Promoting Progress and Prosperity.” It just so happens that this is a subject that is in consonance with the foundational ethos of the Club. Indeed, the Club’s membership which is multicultural, ecumenical and composed of people from diverse backgrounds, is a testament to your commitment to fostering understanding across ethnic, racial and other lines of identity.

The spectacle of so many people of diverse creeds and ethnicities, united by a common purpose and vision, is perhaps the most profound hallmark of the Lagos Country Club. In this sense, the Club is achieving in an understated, but not insignificant scale, the sort of cohesion and civic mutuality that we all aspire to as a nation.

I think that we can also all agree that the subject of my remarks is apt for the times in which we live. We are, as a people, facing challenges that are testing the bonds of our fraternity, unity and our shared humanity.

In parts of the country, we have seen sectarian clashes and insurgency, and immediately after the elections, a rise in kidnappings in different parts of the country. But perhaps the worst threat is from those who would use these challenges to sow discord and division in the nation, by exploiting harrowing tragedies, fanning them into the flames of conflict, manipulating even genuine differences of perspective, opinion and sundry national challenges, as opportunities to promote prejudice, bigotry and strife. That is in my view, the greatest threat of all.

Nigeria is a complex country, composed of over 180 million people of 250 ethnic groups, who speak about 400 different languages and dialects. She belongs to the league of nations, composed of a multiplicity of ethnicities and creeds. It has become commonplace for people to define Nigeria’s diversity as a uniquely problematic attribute that condemns us to perennial volatility and internecine strife on a regular basis. However, we must reject these notions as unfounded. Nigeria is not in any way exceptional or unusual simply because she is diverse.

Mobilizing the people of a country as complex and heterogeneous as ours, under the banner of a common purpose was never going to be an easy task, but this is not to say that it is impossible. Multi-religious and multi-ethnic countries all over the world, grapple daily with tensions that come with diversity.

The United States of America, for example, has a long history of difficult race relations and minority discontent and that is on an on-going basis. Although the motto of the country is, “E Pluribus Unum” which means “Out of many, one”, and is meant to convey the idea of unity in diversity, there are minority communities who see themselves as marginalized and excluded from the mainstream of society.

European nations are confronting the rise of rightwing populism and nationalism and the revival of identities long thought to have been buried under the supranational banner of the European Union and its multicultural aspirations of all of those nations. Immigration is complicating the demographic reality of these nations, unleashing greater diversity, which in turn, carries a greater potential for tension and friction between the different groups.

Today, we hear, almost daily, of the steps that are being taken to restrict immigration in many of these countries and in many of those cases, it promotes tension in those societies.

The rise of xenophobia, nationalism and other forms of chauvinism on the global scene, indicates that the challenge of managing diversity is not just a Nigerian or an African problem. Racial, ethnic and sectarian tensions, are common to diverse societies everywhere. Just as heterogeneity does not condemn a society to perpetual conflict, neither does homogeneity in itself, insure a society against strife. The mere fact that we all speak the same language or belong to the same tribe doesn’t mean that there won’t be strife. In the same way, the mere fact that we all speak different languages or belong to different tribes and religion doesn’t mean there must be strife.

Somalia is probably the best answer to the suggestion that all our national challenges will be resolved by our disintegration into small ethnically and culturally homogenous enclaves. Somalia is composed of just one ethnic group, the Somali, who speak the same language and almost all of them practice the same religion. None of these attributes has prevented her from being mired in conflict for four decades.

A few years ago, many commentators were advocating for the splitting up of Sudan as a solution to its long history of conflict. They called for the disintegration of the country in the belief that such a measure would bring peace to both North and South Sudan who, relieved of the burden of coexistence, would be free to thrive separately. This has not been the case. Instead, South Sudan has been plagued by various conflicts, while its Northern neighbour is reeling from severe political unrest. If the odyssey of South Sudan teaches us anything, it is that by simply separating from people we do not like or people we believe to be fundamentally different from us, is not a solution to the onerous challenge of nation-building in the context of heterogeneous societies. The challenge of nation-building comes with being innovative, patient and being ready to see the greater good.

Everything we have learned from the annals of history and from contemporary reports from all over the world, tells us that social diversity can either be a trigger for conflict or a fountain of prosperity and progress. Diversity in and of itself is not a problem, it is what we do with it that matters. Whether or not socio-cultural variety results in strife or collective success entirely depends on how a society chooses to manage it.

Diversity has the potential to ignite conflict because when elements from dissimilar origins, principles and orientations, meet a measure of tension and abrasion, is inevitable. This dynamic applies regardless of whether the context under consideration is between races, ethnicities, creeds, clans or nation-states.

Prejudice and bias are part of the human condition and are understandable initial psychological responses to any form of plurality. It is very rare to find any cultural or parochial group of any kind that does not have some prejudice against another cultural group. There is nothing innately wrong in people feeling that their cultural group is superior to others. Indeed, many people feel that their cultural group is superior to others; if you ask the Yorubas, they’d tell you that they are the leading cultural group in the whole of Nigeria, if you ask the Igbos, they would say, “there is nothing like us, we are the best”. Ask the Fulanis or Hausas, they would say, “we are pre-eminent”. It is not unusual for cultural groups to believe that they are superior. It would be a lie for anyone to say that they do not have some prejudice somewhere in favour of their own tribe.

But leadership is crucial in determining whether diversity will mean conflict or phenomenal progress. By leadership, I mean the elite as made up of the political, business, religious, civic and social leaders of society. They determine the direction in which their communities go.

Depending on the narratives that the elites chose to propagate, they could either stoke the embers of fear and doubt, or smoothen the rough edges of diversity and pave way for integration. The diverse elements then become building blocks with which to construct a superior collective that produces greater outcomes than the sum of its parts.

When we invoke Nigeria’s peerless potential, as we frequently do, it is the outsized results of such synergy that we are referring to.

So how can diversity and national cohesion lead to prosperity?

It is no accident that the most affluent economies in the world are places that have learned to leverage diversity. In the 21st century, the true wealth of nations is human capital, talent. This means that places that have learned to attract and retain the most diverse pool of skilled human resources are easily winning the race for success.

Diversity means a multiplicity of perspectives and worldviews, but this also provides a broad range of cultural, philosophical and intellectual approaches for solving problems. In this rich soil, nourished by various ideas and schools of thought, productive synthesis is possible and innovation flourishes. Thus, the world’s richest nations today, are those places that have learned how to attract talent from various places and how to harness their diversity as a driver of growth.

One of the more obvious examples of this principle is the United States of America, a nation established by immigrants and that has continued to be renewed by generations of migrants from all around the world. Indeed, the American Dream is widely described as the idea that anyone may come from anywhere in the world, seek fortune in America, and succeed through hard work and determination. America’s global economic preeminence is due in large part, to its longstanding creative management of diversity, but of course, it is not always a success, but it is the best example we can find. It is not a coincidence that global brands like Google, Intel, Yahoo, Mattel and other firms, were either established or co-founded by immigrants or their descendants.

Many Western nations implement immigration policies that actively attract the best talents from all over the world, to bolster their economies. Today, Canada has opened up its doors, it says it wants talent from everywhere and is attracting talent from Nigeria. Canada has you know, has huge land size but very few people. By simply opening up its doors as one of the most advanced economies in the world, it is attracting people from everywhere but it is insisting that it would bring in only persons of proven talent, highly skilled and knowledgeable to make their country better.

When nations have succumbed to shortsighted and narrow-minded policies that victimize minorities, they have learned how not to effectively utilize human resources and they often suffer from all forms of prejudice. Any country that oppresses minorities, promotes practices that further separatism, that country invariably regresses rather than progresses.

For example, when the Ugandan tyrant, Idi Amin expelled East African Indians from Uganda, most of them fled to the United Kingdom and they had a positive impact on the British economy. As for Uganda, its expulsion of the Indians who were the most skilled and economically productive segment of the population compounded the decline of Uganda’s floundering economy.

Similarly, it can be said that America’s ascendancy as a global power in the 20th century gained momentum as it began to accept Jews fleeing anti-Semitic persecution in Europe. Those European societies were run by fascist regimes that violently opposed heterogeneity and sought to implement a racist vision of national purity and homogeneity based on white supremacy. Those fleeing Jews had been part of the intelligentsia in Europe and brought their considerable skills, knowledge and intellect to the nation that had welcomed them and given them refuge. Some of them were instrumental in America’s development of nuclear capabilities and therefore, an important part of how and why the US achieved the status of a super power. The acceptance of plurality by the American society is largely responsible even for its military prowess.

The same principle of diversity and national cohesion must drive economic growth and this applies even in Nigeria. Our most dynamic economic spaces have been historically multicultural cities like Lagos and Kano.

Lagos as a port city, obviously benefitted from its coastal location as a gateway to the African continent for traders and adventurers from beyond the seas, as well as from the hinterland. Kano was a major terminal on the trans-Saharan trade route, drawing commercial traffic from as far north as the Maghreb and the Middle East and from Southern Nigeria.

From the foregoing, it is clear that when we create spaces for migratory talent to flourish without discrimination, there is an economic multiplier effect that results in an ever-increasing radius of growth.

But perhaps there is also a little more to the prosperity of Lagos. In contemporary times, the conscious decision of Bola Tinubu, then Governor of Lagos to appoint his commissioners from everywhere in Nigeria, is partly responsible for the peerless progress of Lagos State from 1999.

He appointed Mr. Wale Edun from Ogun State as Finance Commissioner, Rauf Aregbesola from Osun as Commissioner for Works, Fola Arthur Worrey from Delta as Commissioner for Lands, Ben Akabueze from Anambra as Commissioner for Budget and Planning, Lai Mohammed from Kwara State as Chief of Staff and I, from Ogun State as Attorney General and Commissioner for Justice. In that period, he was opposed by Lagos indigenes, who felt that by virtue of “indigeneship”, they were qualified to be commissioners. They would argue and the argument is always valid, that why should anybody come from “their own State” to come and be commissioners “in our own State.”

Lagos undertook fiscal, real property, judicial and environmental reforms that have made the State a model for the rest of the country today. Today, Lagos State Internally Generated Revenue is greater than the combination of 31 States’ IGR put together. How did that happen? A fiscal reform took place. Tinubu took the best minds that he could find to do the job.

Nigeria is the same nation that produced Africa’s first Nobel Laureate in Literature, Wole Soyinka, Yoruba, of no known religion and Jelani Aliyu, Fulani, Muslim, a world-class designer of motor vehicles. Nigeria is the nation it is because of the collective strength of its many talents, attributes and the various contours of this great country.

How then can we transform diversity into cohesion? I think if properly harnessed, diversity is a powerful driver of economic growth and is therefore desirable. However, as I said earlier, whether diversity leads to conflict or engenders prosperity depends on the extent to which our institutions, promote cohesion and the key to promoting cohesion is inclusion.

In other words, people pull together and work together when they believe that they are part of the same group, when they share a common vision, goal and when they aggregate around a common objective. We witness how Nigerians come together as one when our National Team is playing. Our vision is clear, our objective is certain at those moments, we want our nation to win.

In an earlier generation, institutions such as the National Youth Service Corps and Federal Government Colleges, and later, Unity Schools, were established to foster national cohesion. The essential idea was to take young Nigerians drawn from diverse backgrounds and place them in the same academic and social context located in places far from home.

The goal was to expose young Nigerians to different communities and people, acquaint them with their country’s cultural, geographical and social diversity and in so doing, demystify the sense that the “others”, are different from us and so we shouldn’t associate with them. Such shared experiences are deeply educational because they make it possible for citizens of a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic and multi-religious society to humanize each other.

In the years since these institutions were created, more Nigerians have been exposed to people and cultures different from theirs. I was at an event in Lagos where some old boys of Kings College, a Federal Government college were gathered. So, there was in their midst, Adebayo Ogunlesi, Christian Yoruba gentleman, who founded one of the most successful private capital firms in the world, there was Keem Bello-Osagie, Muslim from Edo State, once a major investor in UBA and Etisalat, Emir of Kano and former CBN Governor, Sanusi Lamido; they were all classmates and they have continued to work together promoting each other over the years. It was a deliberate step taken in establishing Federal Government Colleges ensuring that these young men were able to spend time together, learn together and know that there was no real difference between them and so they have stayed united.

Even working in diversity, take deliberateness and dedication in creating the kind of unity and convergence we want to see.

The challenge for us is to continue to defuse the potential perils of diversity by continuing to pursue measures that promote social inclusion and national cohesion. One of the most important ramparts of national cohesion are the guarantees of fundamental freedoms. The right to life, which comes with it the duty of governments to ensure peace and security, freedom of movement, freedom of worship, and the rule of law. Everyone must be reasonably assured that their lives and livelihoods will be protected by the government, that their disputes will be fairly and justly resolved, regardless of their ethnicity or faith.

This is the main challenge of every diverse society, the assurance of the protection of basic rights and freedoms. Our challenges as a nation basically centre around these issues; religious conflicts, farmer/ herder clashes in the Northcentral and many parts of the Northwest, Boko Haram insurgency in the Northeast, and militancy in the Niger Delta.

When law enforcement institutions are weak, there is a huge opportunity to run divisive narratives. By that, I mean that where, for example, the security agencies do not speedily apprehend criminals, or where the criminal justice system is slow, then there is room for people to say, “they don’t arrest and prosecute Fulani herders when they kill”. It is convenient to forget that there are other people who have committed offences and have not been arrested.

Also, because the law enforcement officers are often not resident in the communities where they are posted for policing duties, it is easier to promote doubt about their commitment to ensuring the safety of the communities they police. This is why policing has to be a communal function, and police officers are required to understand their terrain.

Where the quality and integrity of judges is in doubt, it is easier to find parochial reasons for unfavourable decisions. When you don’t trust or think that the judge is competent, if you get a wrong decision, you will find all sorts of reasons why the decision is wrong. People will say the judge was bribed, it is because the judge is Christian and I am Muslim; there will be reasons for the judge’s incompetence.

The answer to these issues is simple. In diverse societies, we must do all that is necessary to strengthen the institutions of law enforcement, security, the administration of justice and the rule of law. The challenge is dynamic and our approach must also be dynamic. Which is why I believe that State Police in a large and diverse federation is imperative. However, this requires a constitutional amendment, a product of consensus of our legislators.

In the interim, the Federal Government has approved community policing as an option. The IGP recently announced the plan. An important component is that the new approach to police recruitments would be that policemen will be recruited in each local government and after training, will be required to remain in their local governments.

The plan also involves interfaces between traditional rulers, State Neighbourhood watches or vigilante programmes and the police. The security architecture needs to be as domestic as possible, where it favours the use of local persons, local institutions, it is bound to be more effective. The security architecture is now being re-engineered for greater use of technology and more integration of the use of security platforms. A few days ago, the rescue of some persons kidnapped in Ore Benin road and the arrest of the kidnappers was successfully executed because tracking technology and police helicopter were quickly deployed.

Governors of the Southwest States have also committed to purchasing electronic surveillance and tracking systems and patrol vehicles for the use of law enforcement agencies. The coming together of State Governors in the different zones to police the inter-state roads is an important part of keeping security. The various challenges we have can only lead to a situation of rebuilding and strengthening a better security architecture by taking advantage of this current situation. All those involved in the security framework of the country are sensitive to the various issues that are called for.

We must strengthen our judicial system, first by the appointment of judges of integrity and sound legal knowledge. In 1999, when I was appointed Commissioner of Justice in Lagos, we conducted a survey of lawyers who practiced in the Lagos High Court, we took a sample of 200 lawyers and asked them their perception of judges in Lagos State. The options were, “Just and Fair, Corrupt, Notoriously Corrupt”. 89% of the respondents said judges were notoriously corrupt. So, we also asked them what they had done about these judges and no one said anything. Since 1967 when the State was established till 1999, not one Magistrate has been sacked for corruption, not a single judge has been dismissed from office.

We set out to change the system, we decided we would appoint judges differently, it wouldn’t be on a man-know-man basis, we would headhunt and they would go through a series of test and scrutiny from the Nigerian Bar Association. We were conscious of the pedigree and integrity of these judges and we took them through the whole process. We appointed 26 judges in 2001. We took care of their welfare and salaries and improved their salaries considerably. We ensured that judges would have accommodation provided by the State Government. This made a dramatic difference in the quality of judges.

In 2007, a similar survey was conducted by the World Bank regarding high court judges, and the results were that 0% felt that judges were corrupt. It is not to say that people had become saints overnight; first, it was because they were better paid, secondly, in that period, 3 judges had been dismissed, 21 magistrates had been dismissed. People recognized there would be consequences for their actions. It is possible for us to build stronger institutions by a deliberate process of strengthening them and giving people greater confidence in the system and in the protection of their rights before the law.

But beyond maintaining security and law enforcement, we must also clearly, understand the nature of the problems we face.

We must not allow false or skewed narratives, no matter how plausible they may sound. As I had occasion to say (2019 Nigerian Army Day Celebrations on the of 6th July, 2019) elsewhere on the insurgency in the Northeast, and I quote, “since Boko Haram, we have seen other threats emerging. Islamic State West Africa, ISWAP and others in the Lake Chad Islands and parts of Southern Borno. Radical Islamist Terrorism is an evil that must be seen as the common enemy of all faiths, including Islam.

As the President said and I paraphrase, anyone who says Allahu Akbar and goes on to kill is either insane or dangerously ignorant of the tenets of Islam. The likes of Boko Haram, ISIS, Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) and many Salafist-Jihadist ideologies are expansionist ideologies that feed purely on hate; hatred of any person or group that does not belong to their particular sect. They have no redressible grievances, so there are no terms of reference for peace. These are fanatics committed to a twisted creed. They exploit the ignorance of the tenets of Islam, poverty and exclusion, recruit men and women and use children to perpetrate the most heinous atrocities. They are motivated by a satanic desire to control communities by murder and terror.

Whether it is in Iraq, Borno or Syria, their victims are men, women and children, Muslim or Christians, so long as they do not share their sick ideology. They target churches, mosques markets and motor parks where people gather, using children as human bombs to kill randomly, regardless of tribe or faith. I have seen the charred bodies of the dead, men women children killed by suicide bombers, in Gombe, Borno, Kano. The bombs are the ultimate agnostic destroyers. No discrimination in death. The challenge for us is to recognize this extremism for what it is; to form alliances across faiths and ethnicities, to destroy an evil that confronts us all.” It is not an evil that confronts one religion.

This is the reason why in Borno, in the centers of Islam in various places where you find death and destruction, it would then be a false narrative if someone says this is an attack only on Christians. We must understand the nature of the problem.

As Nigerians, we have grown up familiar with the constant habit of some in scholarly, political and journalistic circles making it seem that our diversity by itself is a problem. But it is worth asking whether we are really as diverse as some insist that we are.

There is no denying that we have differences, but the question, are these differences so fundamental as to utterly negate the possibility of cohesion? My answer is no and indeed we must recognize the extent of our shared values. We all esteem the extended family and its corollary notions of welfare and social obligation above unbridled individualism. We share a sociocultural emphasis on solidarity, kinship and community values, which promote the collective interest. All over this country, if we look, we will recognize ourselves in each other because we share the same fundamental aspirations.

A few days ago, I was in Zaria to commiserate with the family of late Precious Owolabi, who was shot during the protests by the Shiites in Abuja last week. His parents have been living in Kaduna State and his father and mother were Youth Corpers in 1990 and married there and lived there. All of the neighbours who came there to mourn are from different ethnic groups and tribes. The parents didn’t move to Lagos to mourn, they remained in Kaduna. All of us, wherever we are from, have the same cares and concerns. All those who gathered there were those who felt the pain of the mother who lost her child. None of them thought it was a light matter because it happened to a man called Owolabi and his wife. They all felt the common pain of that loss.

In fact, I would argue that rather than mere diversity itself being a curse, it is the allocation of access to social, economic and political opportunities on the basis of identity, that is deeply problematic. The problem is not ethnic or religious differences by themselves, the problem is the struggle for opportunities on the basis of those differences. We see this when Nigerians are denied opportunity on the basis of their State of origin or because they are “non-indigenes.” We see it when a Nigerian that has been resident in a State all his life is suddenly excluded from admission into an educational institution or an employment opportunity because he is not considered an “indigene.” Or when a young Nigerian who has served in a particular state during his NYSC year is suddenly excluded from opportunity because he or she is dubbed a “non-indigene” of the State. Not only do these practices undermine national cohesion, but they also feed profound resentments that many people feel.

Honesty demands that we begin to recognize the ways in which we perpetuate institutional discrimination and cause people to see their ethnicities and religions, as weapons for procuring opportunity, often at the expense of others. We must also realize the ways in which our system generates perverse incentives to practice prejudice and undermine national cohesion. Because people are forced to play up their ethnic and religious identities to achieve success, there is a tremendous incentive to deploy identity politics, to be irredentist and to mobilize along even smaller group identities.

Identity politics itself is inherently divisive because it turns people against each other and makes them aliens and strangers. As resources become scarce, identity-based claims to a share of the national patrimony, become more aggressive and lead increasingly to conflict. Under these circumstances, identity politics causes us to see each other as competitors and rivals, instead of compatriots and eventually we begin to demonize each other as “enemies.”

Very frequently, the reason people, particularly the elites, hold on to parochial identities, is because it is a negotiating tool. When a person says “my people have been marginalized”, what he is saying is that “I want an appointment and if you don’t give me that appointment, I am ready to make it seem that a whole people have been marginalized.”

No matter who is president of Nigeria, it doesn’t mean his people would benefit the most. The reality of our nation is that the common needs of our people are the same; they require education, a place to live, job opportunities, economic advancement and it is not served by any narrow ethnic considerations. It doesn’t help and had never helped.

Rwanda experienced a genocidal civil war in the early 1990s. That conflict was rooted in the promotion of differences between the Hutu and the Tutsi by colonial authorities and the subsequent institutionalization of this notion by Rwandan post-independent elites.

When the war broke out in 1994, it was the culmination of many years of simmering animosity between the Hutus and the Tutsis. Over twenty years later, Rwanda has become the poster child for post-conflict recovery and effective governance. One of the things the Rwandan government has done to advance national cohesion is to abolish the ethnic categorizations of their citizens as either Hutu or Tutsi and promote the Rwandan national identity above all other subnational constituencies. Indeed, the use of these ethnic particulars in Rwanda has been criminalized as “divisionism.”

In learning from Rwanda, we have to de-emphasize the elements of our national life that negate cohesion. One of the ways we can do this is by downplaying concepts like “indigeneship” and ultimately erasing it from our national lexicon. The classification of Nigerians as “indigenes” and “non-indigenes”, is our own form of divisionism and has long contradicted our declared aspirations towards unity in diversity. All that should matter in evaluating ourselves, is where we live and fulfill our civic obligations. This is why our Social Investment Programmes are being administered on the basis of residency. The eligible beneficiaries were selected based on their states of residence and none was discriminated against on any basis.

This approach is consistent with our broader philosophy of fostering national cohesion by broadening access to opportunity for all Nigerians without qualification. The framers of the constitution clearly understood the importance of civic mutuality and wrote a number of provisions aimed at promoting national cohesion. Among these constitutional provisions are those found in the Second Chapter on the Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy which stipulates that “National integration shall be actively encouraged whilst discrimination on the grounds of place of origin, sex, religion, status, ethnic or linguistic association or ties shall be abolished.”

The government is further enjoined to “Secure full residence rights for every citizen in all parts of the Federation” and even to “Encourage inter-marriage among persons from different places of origin, or of different religious, ethnic or linguistic association or ties.”

In light of these provisions, it is clear that the promotion of national cohesion for progress and prosperity is a constitutional imperative. I am gratified to note that Kaduna State, for example, to some extent, has abolished all institutionalized discrimination based on the indigene-settler dichotomy and is advancing the cause of common citizenship by making residency the sole basis for providing public goods. This is an important and exemplary step in our pursuit of a country that works for all of us. It may not be perfectly implemented, but that it has become the subject of legislation itself, is progress in the right direction.

Our Federation will never be perfect, nothing organized by humans will ever be, but we must work for a better union; a fairer, more equitable and more just arrangement is possible. We can do better. But that must come from accepting that unity is ultimately more beneficial to all, that unity cannot be justly negotiated under duress, every group must first accept the notion that unity is a desirable option.

As governments, as leaders, political, religious and in business, we can preach a different message. Those of us who preach the gospel of Jesus Christ, cannot be found preaching hate from our pulpits because it contradicts the very essence of our faith. Our faith says we must fight hate with love, we can insist that all children must be fed, children must go to school and have good healthcare whether we are Christians or Muslims, Igbo, Fulani, Ibibio or Itshekiri. We can insist that all our people anywhere, whether in Zamfara, Borno, Benue or Oyo, deserve the protection of the police and law enforcement promptly and decisively.

We cannot condemn killings only when they touch our own because all of us share a common humanity. The death of people is not a mere occurrence, each person who dies means a grieving devasted mother, father, siblings and friends.

Each death demeans all, whether we speak their language or not. The Nigeria of our dreams cannot emerge from tribal irredentism, religious division, identity politics and cultural chauvinism.

There is no Nigerian tribe that does not have its own histories and folklores of greatness and achievement. But none on its own can be as great as this nation of so many and such diversity.

The truth is that any group that suggests that its destiny is outside the Nigerian Commonwealth and so must separate to achieve or realize its ambition will find soon enough that even within that group there are many little splinters, factions waiting to cut the pie into smaller sizes, hoping that by so doing they would eat a larger piece. It is a fallacy that is repeated time and time again.

The enduring truth is simple those who can unite will always be stronger than those who want to go alone. Unity is ultimately stronger than separateness.

Six decades after independence from the British Empire, Nigeria remains a work in progress and is still in many ways, under construction. Nation-building is the task before us and it is not a task only for those of us in government, it is for all of us.

We must create spaces and institutions that nurture a higher sense of inclusion and commonality. Whether in or out of politics, we have a duty to mobilize people in the name of something much higher, greater and nobler, than petty self-serving agendas and parochial, divisive and chauvinistic causes.

As elites, we have a responsibility to see our various sub-national constituencies, not as small mutually alienated fragments, but as elements with which we can forge the sort of grand cohesion that will truly transform our potential into progress and prosperity.

For seventy years, the Lagos Country Club has, in its own small way, served to promote cohesion and peaceful co-existence by providing a recreational haven for people of different creeds and cultures.

As you continue along the arc of your journey, I wish you every success. It is my fervent hope that the ideals of peaceful coexistence, togetherness, fraternity and mutuality, which you have exemplified thus far, will continue to be transposed on a larger scale in our lives and in our nation.

Thank you for listening.

Startrend International Magazine For Your Latest News And Entertainment Gists

Startrend International Magazine For Your Latest News And Entertainment Gists