By Simeon Tegel and Adam Taylor

Former Peruvian President Alan García, under investigation in a corruption scandal, reportedly shot himself early Tuesday as police arrived at his home. (Guadalupe Pardo/Reuters)

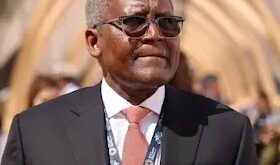

LIMA, Peru — Alan García, the former two-time president of Peru, died Wednesday morning after shooting himself as police attempted to arrest him in the wide-ranging corruption scandal that has implicated scores of leaders in Peru and Latin America.

García, 69, was alleged to have taken bribes from the Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht in return for massive public works contracts. He denied receiving money from the company.

García was a giant of Peruvian politics who overcame a catastrophic first administration in the 1980s — besieged by hyperinflation, the Maoist terrorists of the Shining Path and rampant graft — to win a second term two decades later.

It was for alleged corruption during his second term, from 2006 to 2011, that he faced arrest Wednesday. When police arrived at García’s home in Lima early in the morning, officials said, he told officers he was going to call his lawyer and went into his bedroom.

“A few minutes later a gunshot was heard, and the police forced their way into the room and found Mr. García in a sitting position with a wound to the head,” Peruvian Interior Minister Carlos Morán said.

[Alan García, ex-president of Peru accused of corruption, fatally shoots himself]Day before shooting himself, Peru’s Garcia proclaims innocence

Peru’s former president Alan Garcia shot himself April 17 after police came to arrest him. In an interview the previous day, Garcia said he was innocent. (Reuters)

His sudden death after decades as a public figure stunned Peru.

“Dismayed by the demise of former president Alan García,” Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra wrote in a tweet. “I send my condolences to his family and loved ones.”

It was the latest development in the corruption firestorm that has engulfed both Peru and Latin America’s largest construction company. Odebrecht has admitted paying nearly $1 billion in kickbacks to politicians from Mexico to Argentina.

The U.S. Justice Department fined the company $3.5 billion in 2016, thought to be a global record in a graft case.

Arturo Maldonado, a professor of politics at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, said García’s catastrophic first administration marked a generation of Peruvians, who came of age with their country in ruins.

Police, reporters outside hospital await news of Peru’s Garcia

Peru’s former president Alan Garcia reportedly shot himself April 17 when police tried to arrest him. (Reuters)

His sudden death Wednesday was “traumatic” for the country, Maldonado said, notwithstanding the serious corruption allegations against him, and the widespread sense that he was guilty.

“His death speaks of someone who was cornered, and will be perceived by many as cowardly,” Maldonado said. “The investigation into him also speaks to how the generation of prosecutors once appointed or promoted by García has now become increasingly obsolete. The new generation did not owe him anything.”

During García’s second term, Odebrecht won public contracts worth more than $1 billion. In the final days of his second presidency, he erected a giant replica of Rio de Janeiro’s Christ the Redeemer statue to overlook Lima’s Pacific shoreline, a personal project funded by the Brazilian company as a very public thank-you to the outgoing president. Locals refer to the statue as the “Christ of Odebrecht.”

García’s arrest was expected after anti-corruption prosecutors struck an agreement with Odebrecht executives in Brazil this year that allowed them to testify about their activities in Peru without fear of legal jeopardy.

Prosecutors argued that García was the head of a de facto criminal organization that had laundered money, and a judge signed his arrest warrant. Morán, the interior minister, defended the arrest on Wednesday.

“I want to stress that the intervention by the national police strictly followed the established protocols,” he said.

No country outside of Brazil has been more impacted by the sprawling scandal than Peru, where each of the four previous presidents have been implicated.

Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, the center-right president from 2016 to 2018, was arrested last week over his alleged links to Odebrecht.

His predecessor, Ollanta Humala, the left-leaning former army officer who led Peru from 2011 to 2016, faces trial for allegedly taking illicit campaign contributions from the company. He spent nine months in pretrial detention before he was released by Peru’s Supreme Court.

Centrist Alejandro Toledo, a former visiting lecturer at Stanford University, is fighting extradition from the United States over allegations that he took $20 million in bribes in return for awarding Odebrecht contracts to build sections of the Interoceanic Highway.

Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of former president Alberto Fujimori and herself the close runner-up in the 2011 and 2016 presidential elections, is in pretrial detention to face charges that she laundered secret campaign donations from Odebrecht.

Alberto Fujimori, Peru’s right-wing populist leader from 1990 to 2000, is serving a 25-year prison term on unrelated charges of corruption and human rights abuses.

García, head of the populist APRA party, is arguably the biggest player within Peru to have been implicated in the Odebrecht probe. A gifted orator and political operator, the 6-foot-5 leader long towered over the Andean nation.

His first term, from 1985 to 1990, left Peru touching a historic low. On leaving office, he moved to Paris to see out the statute of limitations on various corruption charges.

He returned to Peru and won the 2006 election — largely because of Peruvians’ fear of the Venezuelan-inspired policies of his principal opponent.

That second term, from 2006 to 2011, saw him plot a conventional economic course as the nation achieved rapid growth. But it was marred by a massacre of indigenous Amazonians and the “narco-pardons” scandal.

In the former incident, dozens of indigenous demonstrators and police died in violent clashes in the jungle town of Bagua over emergency decrees that the protesters feared would open up their rain forest territories to the extractive industries.

In the narco-pardons scandal, a presidential pardons committee personally appointed by García freed hundreds of convicted drug traffickers, including cartel leaders, in return for bribes.

Prosecutors jailed several committee members but cleared García, to the chagrin of many Peruvians.

Those two incidents appear to have defined García’s legacy. He ran again for president in 2016, but finished a distant fifth with less than 6 percent of the vote. Recent polls have shown his disapproval rating hovering around 90 percent.

In November, a court barred García from leaving the country as he was investigated for his ties to Odebrecht.

He publicly declared that he would be delighted to stay in his Andean homeland, but then sought asylum in the Uruguayan Embassy in Lima. He remained there for several weeks before the Uruguayan authorities ruled he was not a victim of political persecution.

García was taken Wednesday to the Casimiro Ulloa hospital in Lima, where he was pronounced dead at 10:05 a.m. The cause was a “massive brain hemorrhage” caused by a single gunshot and associated heart attack, the hospital said in a statement.

“I feel sorry for his family, but killing himself like that is just one more act of cowardice,” said Jorge Layango, 55, a painter in Lima. “It’s the same as when he tried to hide in the Uruguayan Embassy. Now he will never face justice.”

Startrend International Magazine For Your Latest News And Entertainment Gists

Startrend International Magazine For Your Latest News And Entertainment Gists